The Great SaaS Crash of 2026

Software's Two Futures and What Comes Next

What. A. Week.

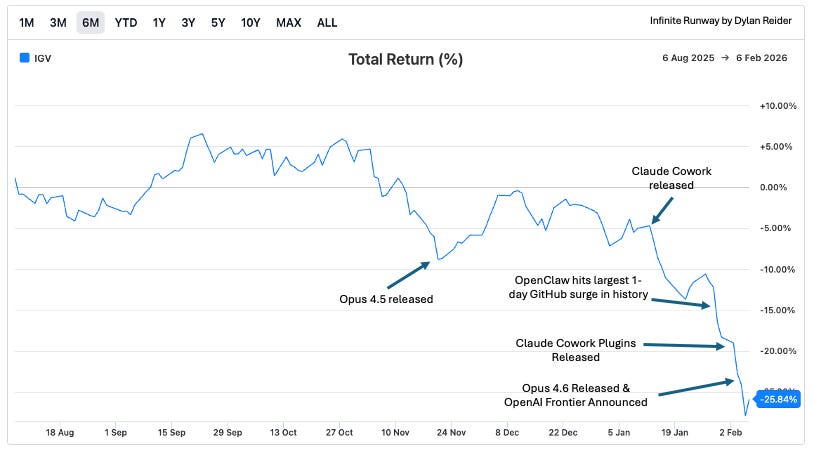

On Wednesday, CNBC host Deirdre Bosa tweeted about how she used Claude Cowork to build her own kanban board interface to manage her to-dos. She tweeted that she wanted to “try to recreate Monday.com”. The tweet went viral, and Monday’s stock traded down 6% on this before recovering and then trading down another 10% Thursday and up 2% Friday.

A journalist built an interface that looks like a feature in Monday, and erased $300M from its market cap in 30 minutes - this is for a company generating $1.3B in annual revenue across 250,000 customers.

But to the market this week, it’s as if Monday was just a kanban board.

That’s where we are today. The “death of software” narrative has grown so loud that the market is looking for any excuse to sell off software. And sell off it did, erasing a trillion dollars of market value.

But the narrative is wrong. Not because software companies don’t face disruption risk from AI (they do), and not because AI isn’t transformative (it is).

The “software is dead” narrative is wrong because it frames the future as binary: Value accrues to either software applications or agents.

After the AI agent architecture advancements of the last two months, it seems pretty clear that Claude & ChatGPT are well positioned to become the default “home screen” for knowledge workers. The main bear case for software in that future is that they become “dumb pipes” that merely provide data to the AI agents to absorb, put into context, and execute decisions on top of.

I believe there is a different architectural path though, and the best software companies are going to have to fight to get there. If you’re a software company clinging to the old paradigm, an expanding TAM will not save you.

Will AI kill software? I don’t think that’s the right question. I think the right question is whether software companies can adapt their products to capture value in the new computing paradigm - or let another company capture that opportunity.

A brief history of the Great SaaS Crash of 2026

It started in November.

Anthropic released Opus 4.5 on November 24, 2025. It was their most advanced model to-date, and the tech world lost their minds over the December holiday break.

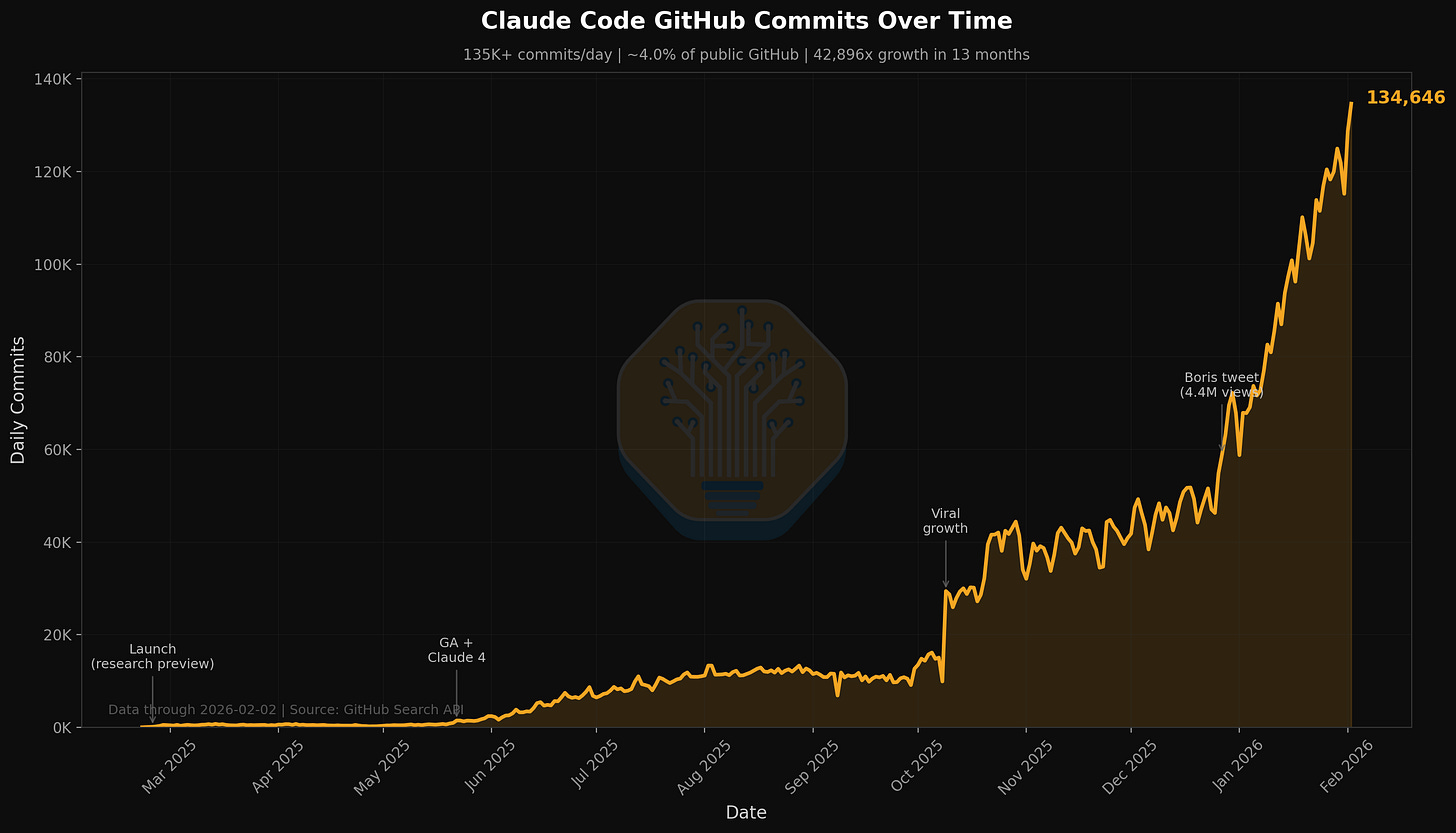

Opus 4.5 enabled a breakthrough in Claude Code (Anthropic’s coding agent) - in the quality, reliability, and usability of the code it generated. It was an inflection point in AI’s ability to ship production-ready code, and you can see it in the data:

The narrative quickly grew beyond just developers, to the idea that everyone should use Claude Code. Lenny Rachitsky wrote a widely-read blog post highlighting potential use cases like finding sales leads, processing meeting notes, and improving writing/brainstorming.

Anthropic brought that idea to life on January 12, releasing Claude Cowork, which gave the power of Claude Code to non-engineers. Then the agent narrative accelerated with OpenClaw’s release a week later (fka Moltbot, fka Clawdbot). Virality ensued and stories exploded across the mainstream press asking questions like, should we be scared?

A big reason why Claude Code, Claude Cowork, and OpenClaw caused such a flurry is they run on your desktop. Meaning they see your apps, your notes, your files, your calendar. That means they have context. And in AI, context is everything.

And on January 30, Anthropic announced they’d provide Claude with a lot more context - with Plugins for Claude Cowork. Plugins are essentially integrations to software systems, plus a set of instructions on how to use those systems. Now the context for Claude Cowork isn’t just what’s on the user’s desktop - it’s data that lives in HubSpot, Workday, Salesforce, Slack, and more (full list here). No need to go into those apps anymore, right?

So to summarize, in this short two-month timespan, AI agents gained three things: Production-ready reliability, viral distribution, and connectivity to the apps that users care about most.

Yesterday poured fuel on the fire, with Anthropic dropping Opus 4.6 and OpenAI launching OpenAI Frontier, a new platform focused on enabling enterprises to adopt agents.

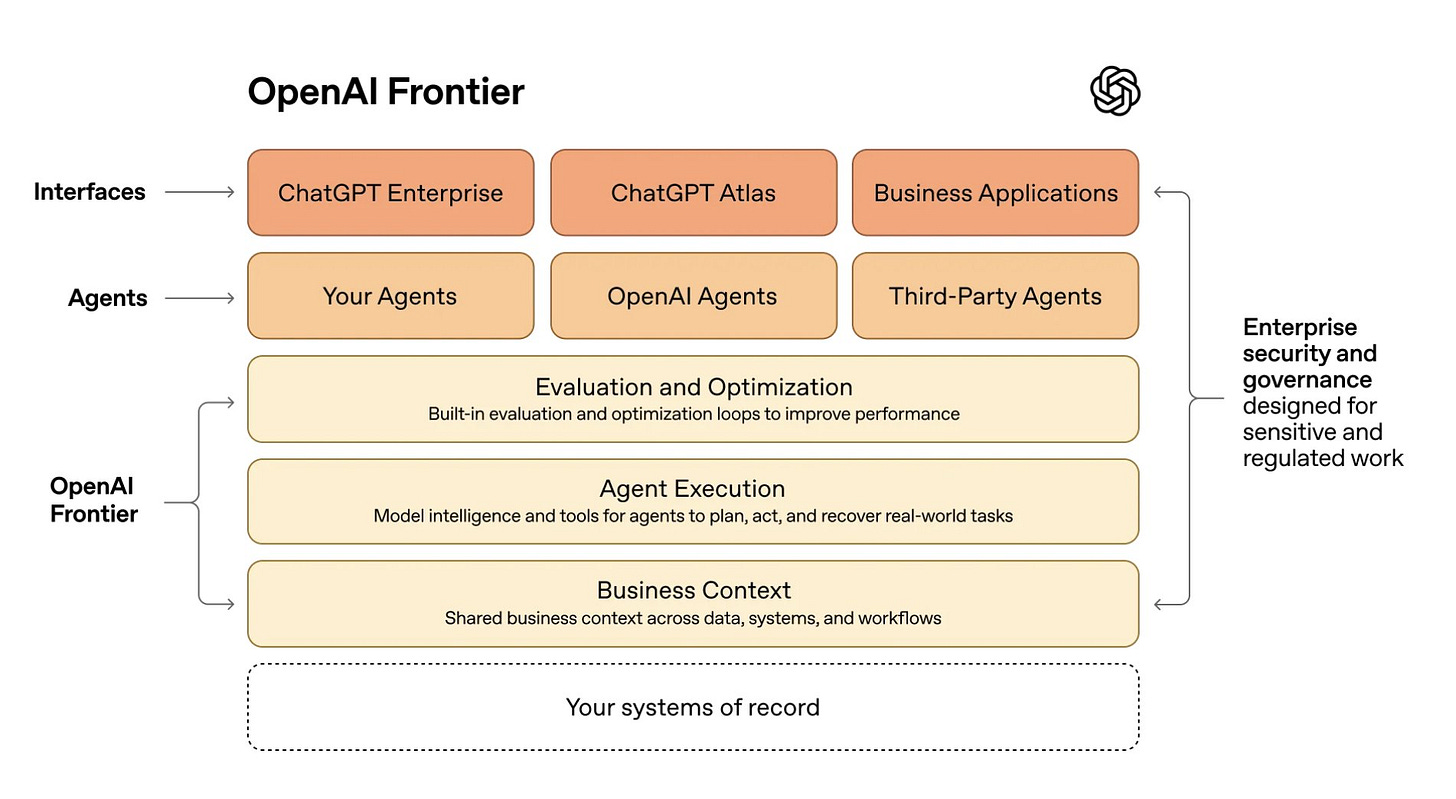

As part of their release of Frontier, OpenAI published this, codifying the SaaS is dead narrative in a pretty diagram:

For software investors, the implications of all this were immediate: If Claude/ChatGPT agents can access my calendar, meeting notes, and Slack, and share updates with my team about next steps after a customer meeting, do I really need to be paying so much to Salesforce? All of the intelligence and business logic will move to my AI agent, so can’t I just use any database to store my customer data, instead of paying so much for a CRM?

In that framing, the system of record just sits at the bottom of application stack as a database that feeds data like a “dumb pipe” to agents that gather context, understand business logic, and take actions on my behalf - then that seems like a pretty unattractive place to be for software! It’s time to SELL, SELL, SELL!

The bear case

Throughout all of last year, there was already a raging debate between bulls and the bears on software. The bear argument has basically been:

Vibe coding erodes moats. When anyone can build software, corporations will just build their own internal tools and competition will compress pricing power.

Fake free cashflow. Stripping out stock-based compensation actually shows many software companies don’t nearly generate as much cash as they seem to be.

SaaS has reached the top of the S-Curve. Corporations have bought so much SaaS in the last decade that IT budgets are essentially fully penetrated, and software industry growth will converge with GDP growth.

Talent costs are spiking. The best engineers want to work for hot AI companies, not traditional software companies. Software companies have to pay up and hurt their profitability, or lose talent to AI-native companies.

Negative reflexivity and capital outflows. Over the last two years capital has flowed out of software and into AI infrastructure, semis, energy, and the mag7. Multiple compression fuels the bear narrative, driving more selling, and creating a vicious cycle with no catalysts to reverse this trend.

These are all interesting arguments, but none of them justify the type of multiple compression we’ve seen.

Vibe coding a kanban board is easy. Building and maintaining the permissions, integrations, and compliance - and the multi-product suite that Monday offers - is a totally different problem, and vibe coding doesn’t solve it. Simply put, corporations do not want to build and maintain their own internal tools.

SBC is high, but it’s not uniform across every company. Software continues to grow well-above GDP and even general IT growth rates, and many software companies are actually seeing growth accelerating. Plenty of smart engineers still want to work at software companies. Finally, negative reflexivity holds until there is an inevitable bottom, even if the recovery takes longer than the bulls would like.

All of that said, there is one bear case that I alluded to at the start of this blog that is very real, and I believe is the principal cause of the current sell-off in software stocks: Value migrating from software applications to AI agents.

If AI agents are the interface between humans and software applications, and the agents contain all context, governance, and business logic, with the ability to read data, execute workflows, and make decisions - then the application underneath will be rendered a commodity database, merely storing data until the agent needs to access it.

That is the real risk that software companies are facing.

Software’s Two Futures

When mobile computing arrived in the late 2000s, humanity’s total computational activity expanded massively, but the companies whose value was tied to the desktop interface suffered. People’s “home screen” moved from their Windows desktop to their iPhone.

Microsoft’s stock treaded water for a decade. It didn’t matter if their theoretical TAM for personal computing devices expanded, because Apple captured that incremental opportunity. Microsoft was lucky that they were able to launch Azure and capture the cloud opportunity even though they missed mobile. Many companies didn’t survive these paradigm shifts.

When Google became the primary interface for the Internet, websites didn’t go away - there are more websites today than in 2000. But it didn’t matter how beautiful your website was, how valuable your users were, or how strong your brand was. Whether you were Nike, Walmart, or Hermes - you were subservient to Google, which captured distribution, discovery, and monetization. Google was the interface layer by which users arrived to your website.

Is the same pattern playing out right now between agents and software companies?

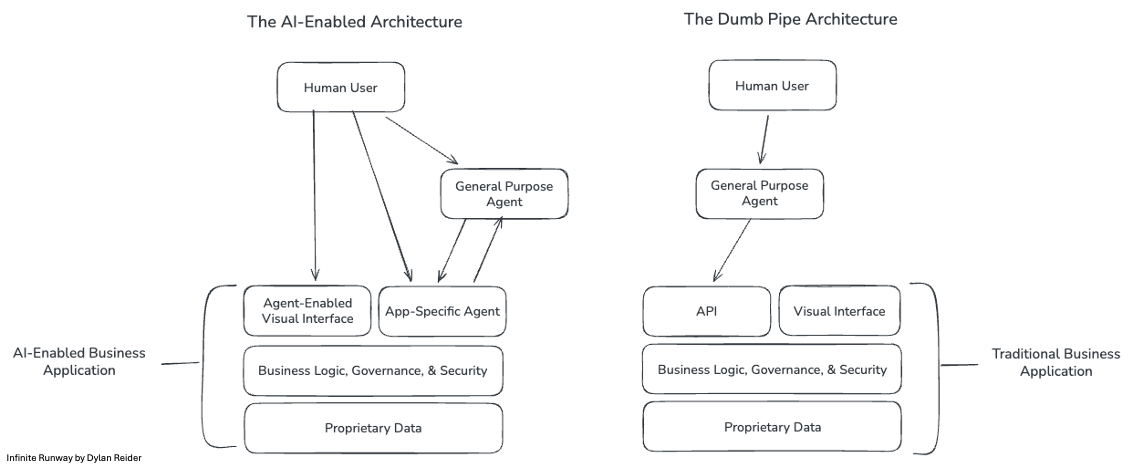

Are AI agents becoming the new interface layer or “home screen” for where work gets done? In the future, will we just access all of our apps via an AI agent that can interact directly with the app’s underlying data, rendering software providers as “dumb pipes” that store data and feed it to agents?

Will they be the version of Microsoft that dismisses the iPhone and misses mobile? Or will they be like the Microsoft that launched Azure despite cannibalizing Windows to aggressively pursue the new opportunity in cloud?

There are two futures for software companies, and they will all face one or the other.

The dumb pipe argument that shifts software companies from the foreground to the background:

A general-purpose AI agent like Claude or ChatGPT accesses my system of record (i.e. CRM) via a plugin or API call, pulls out deal data, drafts a pipeline summary, and sends it to a sales VP.

The sales VP reviews the summary inside of Claude’s interface. The CRM was involved, but only as a source of data. It could be swapped out for any other CRM with an API, or even a database for that matter - and the experience for the end-user would be the same.

The CRM’s differentiation and user-relationship go away, along with their pricing power and stickiness.

This future would be very bad for software companies, and it’s what the current market that is valuing software companies between 3-4x sales is pricing in.

Here is the AI-enabled application future that positions agents inside of applications themselves:

A general-purpose agent accessing CRM via a plugin has shallow context. If the CRM company built a domain-specific agent, trained it on proprietary data from millions of customer interactions, and embedded it inside their application - it would be able to go beyond what a general-purpose agent accessing data via API.

The CRM’s AI agent could tell that sales VP, “this deal is at risk because the customer engagement pattern matches 73% of deals that stalled at this stage across our entire pipeline history.”

The sales VP could then use their general purpose agent to connect with the CRM AI agent, and pull in data from the customer success system and ERP system, to write a customer action plan and contract proposal.

The data in all of these systems is a commodity.

But enterprises don’t just store data inside of ServiceNow - they store governed data. And along with it permission models, audit trails, compliance rules, security policies, intelligence and workflow logic that is non-trivial to configure - that is where the value lies.

Because for a Fortune 500 company that spends 18 months to configure Workday’s permissioning model to match their compliance requirements, controlling who has access to what data and what are they allowed to do with it - is of paramount importance. And a general-purpose AI agent will not be able to inherit that overnight.

If software companies allow all of that value to move to the general purpose agent, they will relegate themselves to merely being providers of that data, and they will become commodities themselves.

The question is whether they let that happen.

The AI-native roadmap

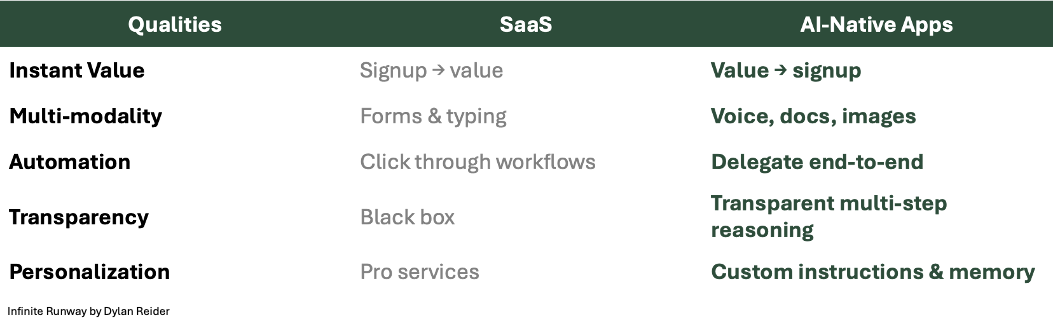

The best AI-native software companies already understand that the future belongs to applications that make agents a first-class part of their interface.

AI-native software companies like Decagon, Sierra, & Kustomer in customer support. DayAI in CRM. Rillet and DualEntry in ERP. And a number of my own investments including Quilr, Qualitate, Rilla, Membrane, Tribble, Quarter20, Dapta, & Coheso.

They are architecting their applications not as passive systems that work well when a general-purpose agent tells them what to do, but rather around the idea that the application itself should be intelligent. That doesn’t mean there’s a chatbot bolted into the side bar, but rather a redesign of how the product works with the assumption that the user wants to delegate tasks to the system.

I think one of the most visceral examples for knowledge workers is Gamma. You describe what you want, their builds it, and you can point to specific components in the deck to have the agent re-work for you. Compare that to Google Slides or Powerpoint (even with their AI copilots), or even asking ChatGPT to make a deck for you.

As I wrote in Raising the Bar, AI-native software products have several ways in which they differ from traditional SaaS applications.

SaaS companies should be as worried about AI-native application companies as they are the AI labs, if not more so.

Even in a future dominated by agents, every company will still need a CRM. But if the marginal company buying their first CRM opts for Day AI over Salesforce, that is going to be a real problem for Salesforce.

Their growth will stall and future will dim, and it won’t be because CRM as a category went away or became commoditized, but because the definition of what a CRM should be has changed.

The Haves and the Have-Nots

If you’ve made it this far, thank you - and now for some stock picks. Just kidding. But hopefully this part helps you navigate the current sell-off in software stocks.

As I wrote about in my Predictions & Themes for 2026, software is going to divide between the “Haves” and the “Have-nots” - companies who are well positioned for AI, and those who aren’t.

Even though the market is treating all software the same this week (as if they’re all going to die), the fact is these companies are not all the same.

There will be software companies who make it through the AI transition, and they will be bigger on the other side. The “Haves” are the ones with the ingredients to build their own AI-enabled future. The “Have-nots” will face a tougher battle.

The Haves. These companies have high gross retention, broad platforms spanning many budget lines, and products that sell to roles that AI empowers rather than roles AI replaces. They have the data, the distribution, and the culture of shipping product to fine-tune their own agents.

The Have-nots. These companies sell narrow point solutions, have relatively higher churn, sell to user bases whose jobs are in the crosshairs of automation, and lack the leadership and culture to ship or buy their way to a meaningful AI product. They lack deep proprietary data.

Certain categories are naturally better positioned: ERP, CRM, customer service, HRIS, CAD, EDA, and other broad systems. General purpose agents need their data, and they have an opportunity to build an agent-powered intelligence layer into their interface. They can own both sides of the stack and be well positioned on the other side of the AI transition.

On the other hand, software companies whose value is in making it easy for humans to interact with their data - an interface layer - these businesses are in trouble. When the agent becomes the interface, there will be little ground for them to stand on.

What comes next

The market is overreacting, but it’s directionally right.

The AI era is massively expanding the surface area of computing. Humans no longer need to be present for compute-intensive work. AI agents will take actions on humanity’s behalf, enable new use cases for technology, and unlock productivity gains we’re only just beginning to see. The total market for software will be far larger in the future than it is today.

But that doesn’t protect software companies from disruption at the hands of AI. Value will shift as agents become a foundational part of the way humans interface with applications.

Software companies that settle for being a plugin will watch other companies’ agents capture their user relationship, pricing power, and market value. Software companies that build agentic capabilities into the application itself, creating an intelligent interface, will come out larger on the other side of this transition.

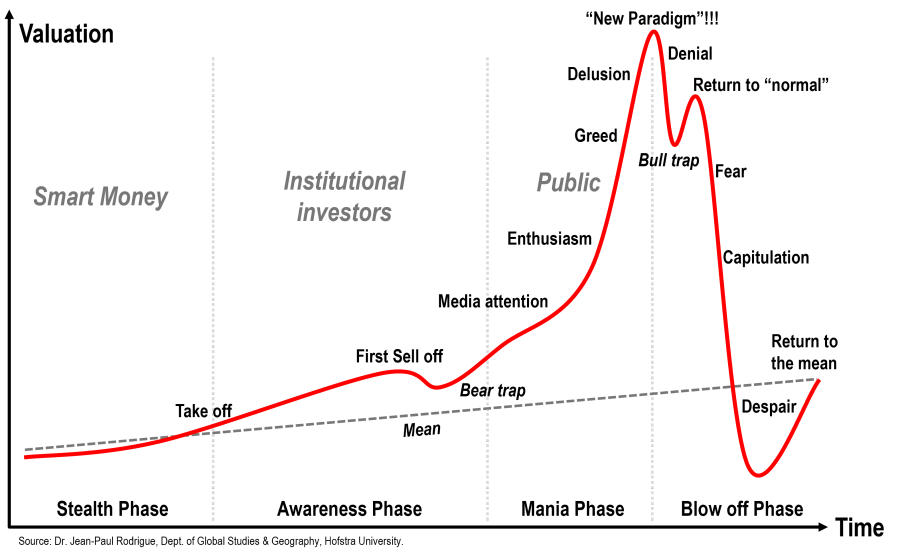

I have no idea if this will be the bottom for software stocks. But it feels like we are somewhere between “capitulation” and “despair”.

The “dumb pipe” argument is a real bear case for software companies.

To refute it, software companies need to:

Embed agents directly into their interface, and ensure their software provides the agentic workflow that their users want.

Tell a clear story to investors of why their software remains as valuable or more valuable in a world where AI agents take digital actions on human users’ behalf.

Back up that story with AI monetization, with clear metrics and consistent disclosure.

Leverage M&A where possible to accelerate their AI-native product portfolio.

Increase cash generation, and right-size SBC and per-share earnings growth.

Stock markets regularly overshoot. Ben Graham famously called the market a manic-depressive, swinging its estimates of a business’s value from wild optimism to deep pessimism. But markets are also the best forecasting mechanism that humanity has - aggregating our collective intelligence into signals about the future. The magnitude may be wrong, but the direction rarely is.

And right now, the market is sending a very clear signal. Investors, founders, and their companies alike should pay attention - there is a clear path of disruption coming to traditional software companies at the behest of AI. It’s also an opportunity. Now is the time to take it.