What is a prediction market?

Polymarket, Kalshi, and the price of the future

In the summer of 2016 I found myself in a small auditorium at Credit Suisse’s New York office for a talk by Michael Mauboussin, who was then the bank’s Global Head of Financial Strategies. He was, and still is, a legend in the investing world.

At the time, I was a summer analyst at a hedge fund, and Credit Suisse had invited a few dozen of their hedge fund clients’ interns to listen to Mauboussin speak.

Mauboussin began his talk by handing a jar of jellybeans to the audience of 100 summer interns. He gave each intern an index card and asked them to write down their guess for the number of jellybeans in the jar, put their index card into a bucket, and pass down the jar of jellybeans and the bucket to the next person.

Over the course of his talk Mauboussin delivered his greatest hits - a series of frameworks for investors covering luck vs. skill, base rates, and culminating in the wisdom of crowds.

At the end of the talk, Mauboussin had one of his associates read out the average of the group of interns’ guesses on how many jellybeans were in the jar.

The average of all of the guesses: 1,162. The actual number of jellybeans: 1,151.

The average guess of the group of interns nailed it within 1%.

Mauboussin used the jellybean jar to explain this idea known as the wisdom of crowds - the power of aggregating many independent views into a signal that can be more accurate than any single participant. That mechanism underlies markets, the economy, and, in many ways, capitalism itself.

My 21 year-old mind was blown. I went back to my office, started researching prediction markets, made an account on PredictIt, and ordered a copy of James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crowds. Much of Mauboussin’s work draws on that book’s core idea: crowds can be highly effective at making predictions when certain conditions are present.

As a venture capitalist, I have been equally fascinated by the rise of Kalshi and Polymarket as I have been frustrated with myself for not having invested in either of them! The two startups, valued in the billions, turn the wisdom-of-crowds theory into tradeable contracts about the future. The price of each contract reflects the probability of an event.

So far the wedge for Kalshi and Polymarket has been elections and sports games - a fun way to make NFL Sundays more exciting.

But their potential runs much deeper.

Prediction markets could become a pillar of the global financial system, as they allow us to get a glimpse of the future.

Their implications for individuals, businesses, and entire economies are huge. So let’s dive into prediction markets - what they are, how they work, and how they stand to impact the economy going forward.

The price of the future

Capitalism, the economic system that brought the world from agriculture to AI, rests on one simple idea - the price mechanism.

A fundamental difference between capitalism and other economic systems is that prices of goods and services are set by buyers and sellers rather than any organization or government.

Under the right conditions, markets are very effective at price discovery - revealing the true value of what a good or service is worth.

Whether we’re talking about the agora of ancient Athens, where merchants haggled over prices of olives and wine, or the modern stock market where high-frequency traders move trillions of dollars electronically - the mechanism is the same: prices that reflect the value of a good or service emerge organically as people trade.

Prediction markets work the same way. Instead of olives or stocks though, participants in prediction markets buy and sell contracts related to future events. Who will win the next presidential election? Will inflation come in above expectations next month? Which movie will win the Oscar for best picture this year? When will the price of bitcoin hit one million?

How prediction markets work in practice:

Prediction markets quote their contracts $0.00 to $1.00.

If the price of a contract “Republican wins 2028 US presidential election” is $0.60, it reflects the market’s belief that there is a 60% probability of a Republican winning.

If you think the true probability is higher than 60%, you should buy at $0.60. If the Republican does win, the contract will pay out $1.00, and you profit $0.40.

Since it’s a market, traders can sell their shares at any time. If the news changes, and shares trade up to $0.65, you can sell your shares at a profit before the election actually takes place.

So by buying and selling these contracts, market participants turn information into prices, and those prices encode probabilities - but it only works if certain conditions are present.

Wise crowds and mobs

Sir Francis Galton is credited with first observing the wisdom of the crowd. In 1907, Galton was at a livestock fair where 800 people participated in a contest to accurately guess the weight of the cow. Galton was shocked to see that the average of the guesses came within 1% of the cow’s actual weight. He wrote about his experience in an article in Nature, remarking “this result is more creditable to the trustworthiness of democratic judgement than might have expected.”

After a century of development in financial markets and economic theory, James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crowds popularized the conditions required for crowds, like the one Galton observed, to have good judgement.

The four conditions under which crowds, or markets, can make accurate predictions:

Diversity of views. Market participants bring different information, biases, and mental models. Diversity makes individual errors cancel each other out, rather than compound them.

Independence of judgments. Traders form opinions without being influenced by each other’s opinions. Independence keeps errors uncorrelated.

Decentralization of information. Knowledge/information about the outcome is dispersed. No single authority dictates the outcome.

Aggregation. A mechanism exists to reliably turn many views into a single signal (i.e. a price). The mechanism should be liquid (lots of traders), transparent (easy to understand what they are betting on), and hard to game (traders can’t single-handedly influence the outcome they’re betting on).

However, wise crowds easily turn into a mob. Five ways markets can break down resulting in poor price discovery:

Homogeneity. When everyone thinks the same way, errors compound.

Centralization. A single authority or narrative drives the market.

Division. Liquidity or beliefs fragment into camps.

Imitation. Investors mimic others instead of making independent decisions.

Emotionality. Fear or euphoria swamps rational valuation.

Inevitably over the course of any market’s history - whether its tulips, stocks, real estate, or Beanie Babies - there will be periods where the conditions for effective price discovery break down. What matters is the market is structurally set up in such a way to support diversity, independence, and decentralization.

Okay - enough theory. Let’s dig into modern prediction markets and where they’re going.

Prime Time

The first modern prediction market was launched in 1988 at the University of Iowa. The Iowa Electronic Markets (IEM) has been running for almost 40 years, regularly outperforming polls at predicting outcomes of elections. Along the way, prediction markets garnered increasing attention with small platforms like PredictIt, but they were mostly confined to academia and small studies.

That changed in 2020, with the launch of Polymarket, and the subsequent launch of Kalshi in 2021.

Polymarket was first to take prediction markets on-chain, launching the first blockchain-based prediction market.

How it works: Traders bet on an outcome with USDC. When the the outcome is settled, an independent checker known as an “oracle” in the crypto world, looks at public sources and determines what happened (i.e. which team won the game). Once confirmed, the software automatically pays out USDC to the winners.

Their core innovation: Polymarket applied the blockchain’s trustless verification to prediction markets, replacing a middleman with software.

Kalshi’s approach focused on regulation, launching the first prediction market regulated by the US government.

How it works: Overseen by the CFTC, Kalshi is a fully regulated U.S. exchange. It allows traders to trade in dollars, and they put up money in advance to ensure guaranteed payouts. A centralized system, similar to those that power commodity exchanges, ensures that traders get paid correctly. Each contract has an official data source cited to publicly determine outcomes of an event (i.e. citing the Bureau of Labor Statistics for inflation prints).

Their core innovation: Kalshi’s was the first fully regulated US prediction market.

While Polymarket doesn’t (yet) charge trading fees, Kalshi does have trading fees and withdrawal/deposit fees.

Kalshi’s last valuation was $2B, backed by Sequoia and Paradigm. Polymarket’s is $1B, backed by Founders Fund and General Catalyst, and rumored to be getting interest at higher valuations.

Other companies are taking note and launching their own prediction markets, from juggernauts like Robinhood to startups like ProphetX.

Sports and politics have been the wedge so far. The US election last fall saw massive trading volume, and football season will likely drive another season of growth.

It makes sense - betting on sports and politics is fun. People care, they have opinions, and they can talk about it with their friends.

Plus, sports betting in America generates hundreds of billions in annual trading volume and $10B+ in net revenue for betting/gambling platforms. That is a big pie for prediction markets to eat into - and grow - by making betting more accessible.

A less appreciated, and potentially transformative opportunity for the prediction markets isn’t with consumers, however. It’s with institutions - businesses, investment firms, and multi-national corporations.

From Bets to Budgets

Managing risk is a core part of any business or investment firm. Idiosyncratic shocks like war, natural disasters, economic depressions, or even small changes in crop prices or supply chain disruptions can have major negative consequences to businesses.

Helping those institutions hedge those risks is a massive business today, dominated by exchanges like the CME, clearing houses like LCH, and banks like JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs. These organizations offer derivatives, futures, options, and other financial instruments that help corporations offset unwanted moves in interest rates, currencies, commodities, and more.

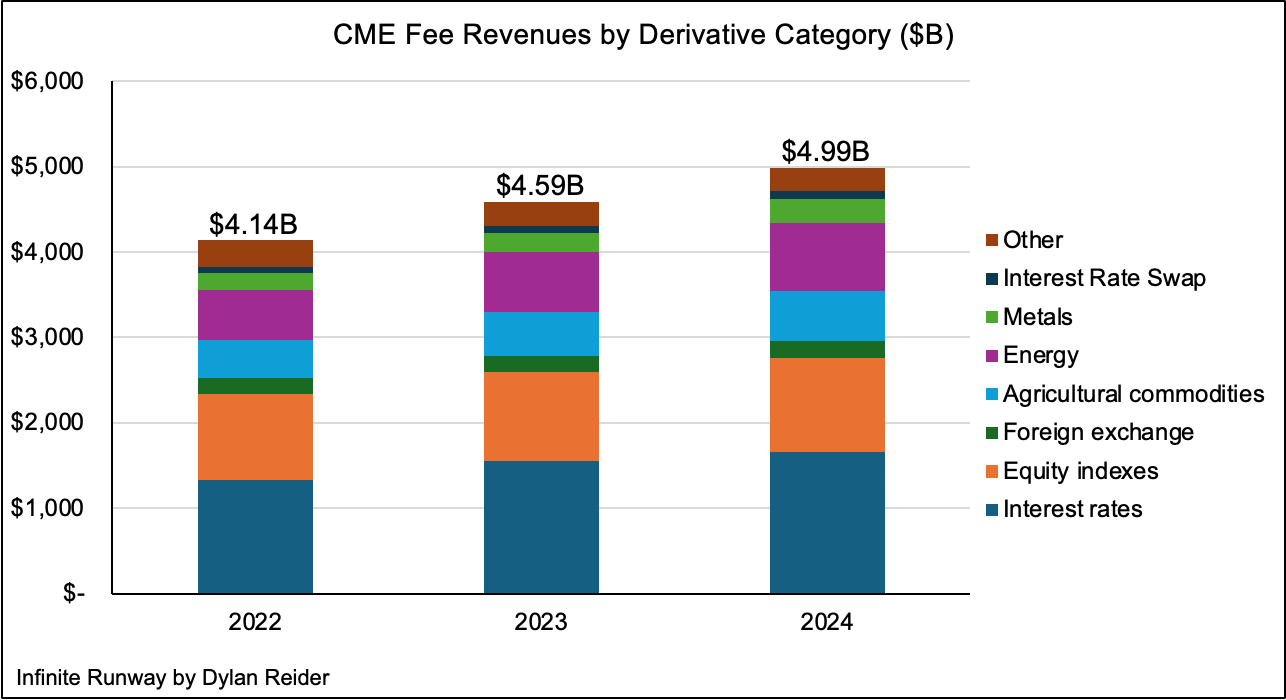

To give you a sense of scale, the largest derivatives exchange in the world, the CME, generated $5B in revenue last year tied to fees from its derivatives.

Off its total revenue base of $6.1B last year, the CME generated 64% operating margins and 57% net income margins. Its market cap is just shy of $100B.

It may not be a hyper-growth AI company, but that is quite a good business!

However, most derivatives aren’t traded on exchanges like the CME. The overwhelming majority of derivatives are traded in what are known as over-the-counter (OTC) transactions. These are privately negotiated deals between the buyer of a derivative (i.e. a corporation or investment firm) and a counterparty like a bank.

So the opportunity for prediction markets to get into institutional hedging is actually much bigger than just taking share from CME and other derivatives exchanges. It’s also about going after the OTC market, and the tens of billions of dollars of revenue generated by investment banks and other counterparties.

Prediction markets have several advantages over traditional hedging via OTC derivatives. They allow for better precision, with contracts tied to specific events. Bespoke OTC derivatives often take weeks to spin up, with meaningful legal costs, whereas prediction markets can offer broad catalogues of contract offerings. Being cloud-native with modern infrastructure should also enable prediction markets to offer high quality data feeds and APIs - which gets to our second institutional market opportunity for prediction markets.

Selling the Tape

Just as Robinhood monetizes via payment for orderflow, Kalshi and Polymarket have the potential to launch large data businesses. Kalshi has already launched an API.

As prediction markets continue to scale their market catalogues across macro, crypto, elections, and more, institutional investors will want access to that data. Small changes in the prices of these contracts could serve as a valuable predictive insights to investors and corporations.

By comparison, CME generated $710M last year from their market data business.

What Could Go Right?

Prediction markets have gone from small, academic curiosities that test fundamental principles of economics, to become major businesses that drive billions of dollars in trading volume every year. And it’s only the beginning.

Real tailwinds are propelling the growth of prediction markets. Retail investors are only becoming more numerous as society becomes wealthier and more online. Regulatory relationships support legitimacy and institutional trust. Polymarket and Kalshi have barely scratched the surface of the thousands of contracts they could potentially expand into. And the market opportunities from institutional hedging and selling data via API can be even bigger than their consumer businesses.

They have a long way to go, but Kalshi and Polymarket are already starting to put together the building blocks of a global financial market - deep liquidity, regulatory relationships, strong brand, and infrastructure required to handle scaled trading volume.

As they continue to expand the types of contracts they offer and the complexity of transactions they can handle, the combined consumer + institutional market size for prediction markets could be a revenue opportunity measured in the tens of billions.

From jellybeans to elections, prediction markets tell us what might happen tomorrow, and that’s a price worth watching.