Outsiders, Insiders, and Founders in the AI era

What SaaS Founder Backgrounds Tell Us About Building Companies in the AI Era

As AI reshapes software, investors and founders are constantly looking back to previous technology cycles - the shift from desktop to mobile computing, from on-premise software to SaaS and the cloud, and the creation of the internet.

Looking at past tech cycles shows that disruption often follows similar patterns, and by learning from them, we might be able to better spot the innovations that change the future.

I was recently listening to a podcast with Eric Vishria, a general partner at Benchmark, and for my money one of the top venture capitalists on the planet. Vishria made a compelling observation of what drove success among software companies in the early 2000s in the beginning of the SaaS era:

“In the SaaS world, over and over again you had people who really understood the customer and the problem, and understood the domain and what the technology was capable of. But it was not a question of if you could build something…CRM existed before Salesforce…Salesforce followed Siebel, Workday followed Peoplesoft, ServiceNow followed Peregrine and others. So they were cloud/SaaS versions of the prior product, which was on-prem…They understood the customer problems and took advantage of the next wave…Most of the V1 SaaS companies, they weren’t so crazy - we run this product for you and make it better, web-based.” - Eric Vishria on The Peel with Turner Novak (link)

He makes two points:

Successful SaaS founders had deep domain expertise, understood their software market, and the problems customers faced.

They were able to leverage that expertise to port over products that were successful in the on-premise software era, rebuilding them as SaaS.

Vishria went on to contrast the type of founder that was successful at the beginning of the SaaS era, with the type of founder that is successful today in the beginning of the AI era.

“…product development happened in [in the SaaS] cycle…almost diametrically opposite of product development in the AI era. I look at the teams that are having the most success today, and they have intimate knowledge of the models. They are right on the frontier of understanding which models are better at what, and why, and when, and what they’re gonna be good at and what they are not gonna be good at. And they are spending their time on, how do I apply this model to this domain, or to this user? So they are working technology out rather than customer problem in. They are really close to the metal in terms of capability and are applying it out.” - Eric Vishria on The Peel with Turner Novak (link)

Vishria claims that the most successful AI founders today, rather than being domain experts, are experts in the AI models themselves.

Contrasting early SaaS founders as domain experts versus early AI founders as technology experts is a fascinating observation.

No doubt many of the early SaaS successes like Salesforce and Workday certainly match Vishria's two points. Their founders understood their category, had expertise from the on-prem era, and used that experience to build their SaaS company.

Yet other SaaS pioneers, like DocuSign, HubSpot, Unity, Akamai, or Olo - all of which were founded in 2006 or earlier, didn't neatly fit this pattern. Their products represented new market categories, and not all of their founders previously had narrow domain expertise or founding experience.

So, looking beyond these anecdotal examples - what does the data say? Do SaaS founders tend to be repeat entrepreneurs who possess deep domain expertise? Were SaaS ideas often replications of previous iterations of software in the on-prem era? And what can we learn from these questions as we enter a new era with AI?

Founder Backgrounds in the SaaS Era

To start to try to answer these questions, I pulled together a dataset of 90 publicly traded SaaS companies1, and tried to uncover common patterns in their founders’ backgrounds.

Surprisingly, the data suggests there is no clear pattern.

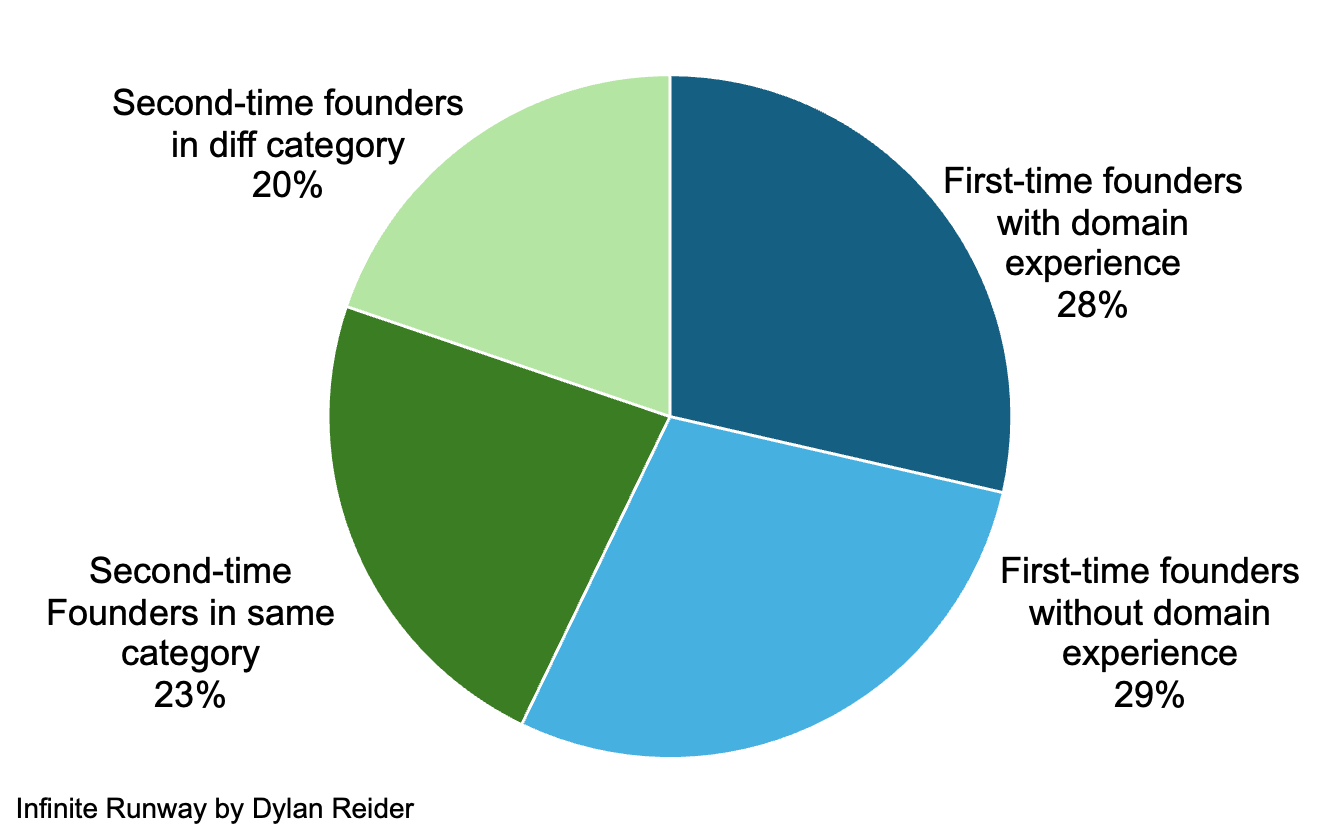

57% of the companies in the dataset were first-time founders, and 43% were second-time founders. 51% came from the same category of software in their previous job, either as a founder or not, and 49% came from a different category of software (or a different industry altogether).

I took the analysis a step further and added a time component. Do founders of a particular background become more or less prevalent as the SaaS wave continued over last 25 years?

Surprisingly again, there was no clear trend or shift over time.

Correlation between founding year and second-time founders: 0.12

Correlation between founding year and domain experience: 0.16

Remaking the old and inventing the new

What about the idea that it was more common in the beginning of the SaaS wave (2000-2006) to see companies that were a direct “port” of an existing on-premise software category?

For each of the 90 companies, I marked whether its core product was a direct SaaS re-creation of an existing on-prem category or represented an entirely new, cloud-native innovation. The results showed a moderate negative correlation (-0.3) between founding year and the likelihood of being a “ported” category.

In other words, the more recently the company was founded, the more likely its category is cloud-native, and did not exist prior to the SaaS era. As the SaaS wave matured, re-architected legacy categories gave way to entirely new, cloud-first innovations.

SaaS-native companies like Snowflake, MongoDB, Twilio, GitLab, ServiceTitan, Monday.com, UiPath, Samsara, and many others created product or technical innovations that created new categories of software. Even if they rhymed with previous generations of software, they were not recreations of on-prem products.

While a correlation of -0.3 is moderate, the trend reflects the evolution of SaaS from modernizing legacy on-prem tools to unlocking new use cases made possible by the cloud.

Which brings us to AI.

Implications for AI founders Today

There are interesting implications here for founders today building AI companies.

Similar to how early SaaS pioneers like Salesforce took established on-prem products (like CRM) and moved them to the cloud, today's AI startups are 'AI-ifying' existing SaaS products.

Companies like Day.ai are trying to replace Salesforce, building an AI-native CRM. Gamma is trying to displace Google Slides in slide deck creation, and Decagon and Sierra are trying to displace Zendesk in customer service software.

Some of these companies “AI-ifying” old software archetypes will work, and many won’t.

A big outstanding question is whether AI will prove to be a disruptive innovation or a sustaining innovation. In The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Cristensen highlights how sustaining innovations can be weaponized by incumbents to sustain their leading market position, versus disruptive innovations which can empower startups to disrupt incumbents. The internet was a disruptive innovation, enabling Amazon to disrupt the retail industry and Google to disrupt the ad industry. Mobile was largely a sustaining innovation, leveraged by Google, Apple, and Meta to further entrench their competitive positions (though there were new disruptive players like Uber and AirBnB).

In the software industry, SaaS was a disruptive innovation because it changed the business model, delivery model, and pricing model of software - from up-front payments for software code on a server to a subscription for applications accessed via the web.

There is a strong argument to be made that for much of software, AI will be a sustaining innovation. The incumbents like Salesforce and ServiceNow are all over AI, making acquisitions and adding new AI products, and aggressively pushing them onto their customers. Today’s tech CEOs have all internalized the The Innovator’s Dilemma, and they don’t plan on losing market share.

Rather than focus on existing categories with incumbents, there is a more exciting opportunity for startups to think about new capabilities that AI models that will deliver, which can create entirely new categories of software. What industries lack software can benefit from AI? What new problems will exist in the future because of AI, that can be solved through new AI-enabled software?

Here are a few AI-native categories that I’m particularly excited about, with some example companies:

AI-generated media - Synthesia, Midjourney, Pika, ElevenLabs

Disrupting traditional video production, visual effects, and graphic design by eliminating the need for film crews, professional actors, specialized VFX artists, and expensive studio tools

Legal AI - Harvey, Legora, Coheso

Disrupting labor spend on junior lawyers, and software spend on legal project management tools

AI-powered surveys - Qualitate, Listen Labs, Ethos

Disrupting expert networks like GLG, and survey software like Qualtrics

Industry-focused AI note takers - Abridge, Rilla

Disrupting manual note taking, voice note recording, and industry-specific workflows

AI-automated security event resolution - Cotool, Dropzone

Disrupting labor spend on junior security analysts focused on managing alerts and notifications

AI-enabled recruiting platforms - Mercor, Paraform, Candix

Disrupting recruiting agencies and manual candidate sourcing

AI-Powered Sales Enablement - Glean, Tribble, Docket

Disrupting traditional sales playbooks, manual research, and legacy enablement platforms

Like art, technology constantly builds on its own history, so even AI-native categories reflect patterns from earlier software eras. What sets them apart is that AI now enables entirely new solutions and experiences that simply weren’t possible with previous tools, expanding the boundaries of what software can do.

My data set included 90 publicly-traded SaaS companies. I defined SaaS companies as only including companies founded post-1997. So I excluded companies that were originally founded in the on-prem era and transitioned to SaaS companies, like Microsoft, Adobe, Oracle, and SAP. I also excluded companies that sell hardware and software, like Palo Alto Networks, Cisco, and F5. I did not include any private companies.

Of course, any data set has limitations. My data only includes companies that made it to IPO, a significant survivorship bias that excludes thousands of SaaS startups either failed or stayed private. The data also does not include whether or not the founder stepped down as CEO and brought in someone else to scale the business at a certain point.

Amazing!!!! So insightful