Raising the Bar

How ChatGPT is reshaping what users expect from software

Welcome back to Infinite Runway, my newsletter on tech, startups, and investing. If you haven’t subscribed yet, you sign up below.

In 2011 I purchased my first stock, Amazon. In two years, I doubled my money, sold it, and felt ready to leave my freshman year dorm for Wall Street. Then, the market taught me a lesson. I watched Amazon’s stock continue to rise, along with my regret for selling it. I sold too early, the first in many mistakes that I’ve made as an investor. If I held through today, it would have been an 18x investment. But that isn’t what this post is about.

Fidelity, my brokerage at the time, charged me $7.95 to purchase Amazon’s stock, and another $7.95 when I sold it. Brokerages like Fidelity, E-Trade, and Schwab charged these hefty fees to consumers to facilitate transactions in stocks and other investments. Then in 2015, Robinhood launched its mobile app in the App Store. For the first time, consumers could buy and sell stocks without paying transaction fees. That value proposition resonated with consumers, and 4 years later Robinhood crossed $35 billion in assets under management and $270 million in revenue. That same year, in 2019, Schwab, E-trade, and Fidelity all announced fee-free stock trading in an effort to stem the bleeding of market share loss among young investors that were turning to Robinhood’s free and easy to use mobile app. The $7.95 transaction fee I paid to buy Amazon’s stock in 2011 would be unthinkable today.

One reason I bought Amazon’s stock was that I was a frequent customer. I loved video games as a kid, and Amazon offered a more convenient way to convince my parents to buy me a video game than asking to be driven to Gamestop. That convenience stemmed from the customer-obsessed culture that Jeff Bezos imbued in Amazon from its founding, and it manifested in the company’s continual push to cut delivery times. It began with 2-Day shipping that was announced in 2005, as Amazon unveiled its Prime subscription for $79/year. In 2009, it piloted same-day delivery in seven US cities, and over the years Amazon rolled out Prime Now which promised deliveries in hours. By 2019, Amazon announced one-day shipping would become the norm across millions of goods for most Prime households in the US. With each iteration, competitors scrambled to keep up. Two weeks after Amazon’s 2019 announcement of one-day shipping, Walmart announced next-day delivery.

Capitalism relentlessly reshapes consumer expectations. Technological marvels from microwaves and dishwashers, to smartphones and self-driving cars, start as miracles but quickly become invisible staples of everyday life.

Amazon and Robinhood are two examples of companies, which every once in a while, introduce society to a product or service that is so radically better than what we’re used to, that it resets our entire sense of what’s normal.

We are just beginning to feel it, but ChatGPT has begun to catalyze the next big reset in consumer expectations. AI generally, but ChatGPT specifically, is raising the standards that users demand across every digital experience they have. The implications will ripple across the economy, but be felt most immediately by software vendors.

The fastest growing app of all time

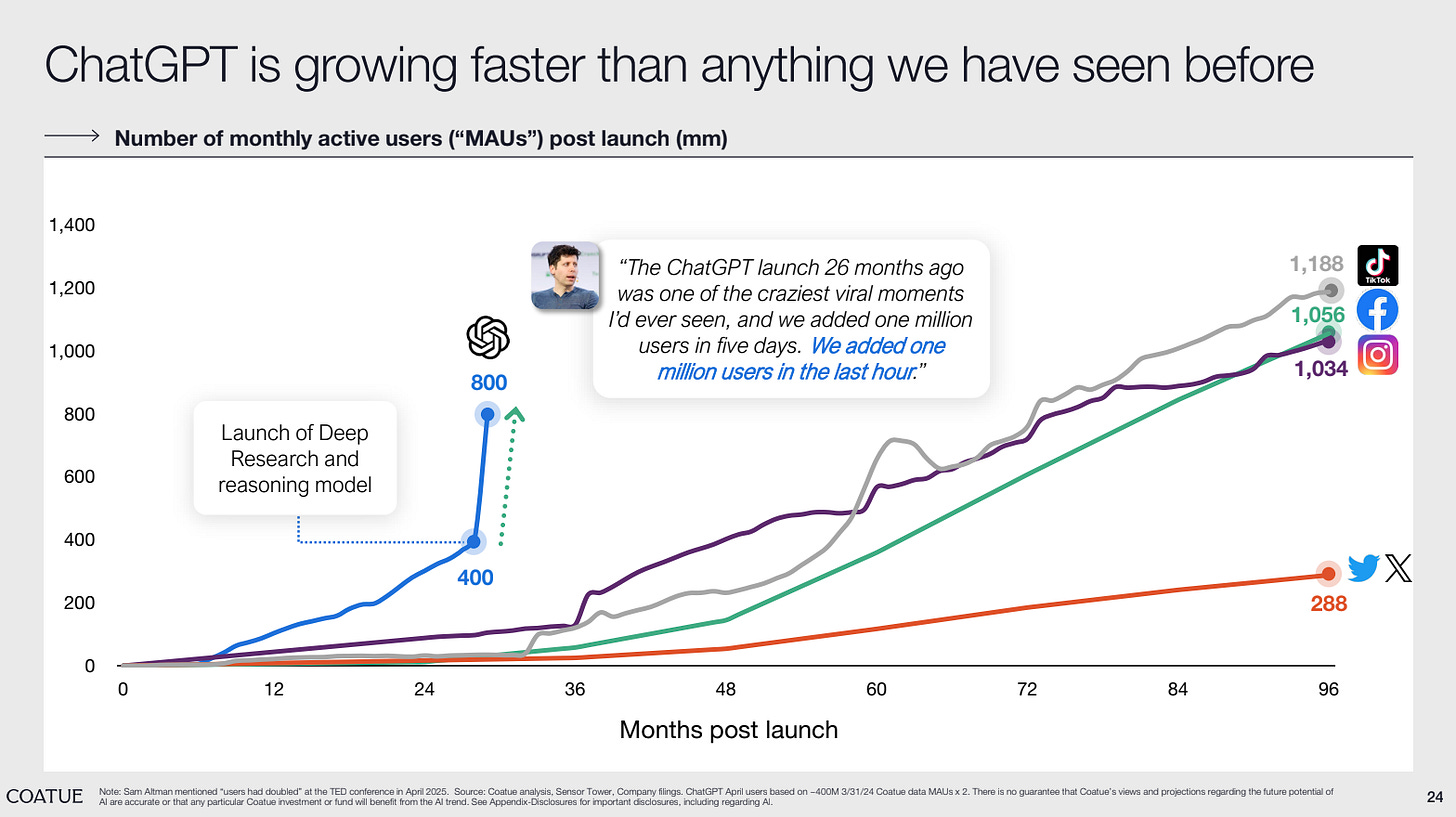

ChatGPT is the fastest growing software application of all time, and it’s not even close. As the slide below from Coatue’s East Meets West presentation shows, it’s on track to reach a billion monthly active users in half the time of the most successful consumer apps, like TikTok, Facebook, and Instagram.

Monthly users are impressive enough, but ChatGPT has already amassed over 100 million daily active users. AI is transitioning from being a productivity-boosting answer engine, to an intelligent assistant that we carry around with us every day.

And that daily habit is where the innovative novelty becomes invisible.

When consumer standards change, so does software

In 2001, Douglas Neal and John Taylor, two tech industry research analysts, coined the phrase “the consumerization of enterprise IT”, to talk about how business software would increasingly look like consumer software. Their hypothesis was that everything from the software itself, to how its consumed, purchased, and priced, would start to look more like consumer software. Neal and Taylor were prescient in their prediction, as the consumerization of enterprise software became a distinguishing feature of many of the software companies that rose to prominence in the 2010s.

Arguably the biggest catalyst of bringing Neal and Taylor’s 2001 prediction to reality were mobile-native applications like Robinhood, Uber, and Airbnb, which set new standards in the simplicity and intuitive design of digital experiences. Many B2B software companies followed by creating disruptively simple and beautiful product experiences, such as Monday.com, Figma, and Airtable.

It didn’t just stop at product design. The way companies purchased and procured software also changed, with increasingly empowered teams and departments allowed to purchase their own software without approval from a centralized IT department. Companies like Slack and Zoom, and even earlier Atlassian, benefited by offering product-led-growth sales models that allowed users to adopt their software as easily as downloading an app from the app store.

Pricing models became more transparent in the 2010s cloud era. Historically, software pricing was negotiated behind closed doors. Vendors like IBM and Oracle typically quoted custom prices based on factors like deployment complexity, licensing structures, maintenance agreements, and number of seats, often varying widely between customers. Today, most software companies have pricing pages on their website that outline clear subscription plans, or pay-as-you-go usage-based pricing.

Not all parts of the software industry were impacted by this change, as enterprise buyers tend to be risk averse. Putting in new systems often means ripping out old ones, which comes with risk they are related to core business processes. Legacy ERP (enterprise resource planning) vendors like SAP and Oracle, who sell financial management software to large enterprises, have benefitted from this, as the only 2010s-era company that truly encroached on their market dominance in ERP was Workday.

That said, most of the software industry today is dominated by companies that bring some elements of consumer-grade digital experiences to their enterprise users. Modern software vendors build products that look and feel intuitive, don’t require a lot of organizational process to integrate into their business, and have clear pricing models.

How AI will reset consumer standards (again)

Just like the cloud/mobile era of the 2010s saw innovative companies reset the standard that people have for software both in and out of the workplace, AI is driving the next reset in expectations, and doing so at an unprecedented pace.

Instant value. AI is collapsing consumer patience for answers the same way that Amazon collapsed consumer patience for packages. ChatGPT allows users to ask questions without signing up, just ask a question and get an answer. To take advantage of more complex features like memory and personalization, users need to create an account and sign in, but even without that they can get value - and more importantly understand the value that ChatGPT delivers to them - immediately.

Automation. Users will increasingly begin to expect software to anticipate their needs. In the next several years, as AI agents gain the capability of navigating the internet and executing tasks on behalf of users, manual data entry will become a thing of the past. Whether it’s booking travel or updating a CRM, software will become increasingly autonomous.

Multimodality. One of the mind-blowing features of ChatGPT that has been under-appreciated is its ability to seamlessly move between text, voice, and video. Software will increasingly be able to execute complex tasks via voice - delivering on the promise that Alexa and Siri offered users a decade ago.

Transparency. DeepSeek shocked the world in January this year with its R1 model. While the focus was on how a small company could seemingly come out of nowhere to produce an OpenAI O1 level reasoning model, arguably the most lasting impact DeepSeek had on the industry was showing the model’s step-by-step reasoning to the user in the app - a feature that has now been rolled out to other reasoning models from ChatGPT, Claude, Grok, and other model providers. As AI is increasingly tasked with handling complex tasks, consumers and businesses will want to be able to retroactively audit its decision-making process. Especially when things go wrong.

A generational opportunity

We are living through AI’s Goldilocks moment. Its a window in time that we will look back on as being unique for AI adoption. Budgets are loose, curiosity is high, board rooms are mandating AI plans, and society is only just beginning to adapt to a world where intelligence is a commodity.

Right now, ChatGPT is reshaping what users believe software should be able to do: instant value, intelligent automation, multimodality, and transparency in decision-making. Before long, these will move from being sources of differentiation to table-stakes.

This will happen fast, and while most large software companies pay lip service to shipping new AI products, many will prove to be surprisingly slow in shipping products that create truly game-changing user experiences. For startups, opportunity is clear to become the next generation of companies that raise the bar for the rest of their industry.